Even before COVID-19 reshaped the way the world moved, our team at Via was helping to address the many challenges of our time: climate change, social inequity, and urban gridlock among them.

Bold solutions like technology-enabled, dynamic, demand-responsive transport (DRT) are needed now more than ever before to preserve public transport and rebuild riders’ trust. These systems lead to overwhelmingly positive results — the dramatic ridership increases, greater efficiency, and reduced costs are indisputable. Yet still, many communities are apprehensive about DRT, and some leaders aren't convinced that it can help mitigate local challenges on the ground.

They need to see it to believe it. That’s why we’ve rounded up some of the most common misconceptions that partners have shared with us before embarking on very successful DRT journeys.

MYTH: DRT is expensive. We can’t invest in something that isn’t financially viable.

Reality: When DRT is implemented in a smart way, communities can actually save money compared to their previous fixed-route services, unlocking broader benefits that pay back the initial investment many times over.

Providing high quality services at the minimum possible cost to the taxpayer is the right starting point for any local authority. However, that doesn’t mean that public transport innovation must be profitable in order to benefit communities. While the UK is a highly commercial market, a significant (though declining) number of bus services are supported. This was the case prior to COVID-19, and services will need even more support as we emerge from the pandemic.

Therefore, the question to ask is: how can we provide the most cost-efficient service where the commercial market is not viable? Our experience is that DRT, when implemented in a smart way (particularly merging duplicative services into one scheme), can be a lower cost option than fixed route services while demand is low and uncertain.

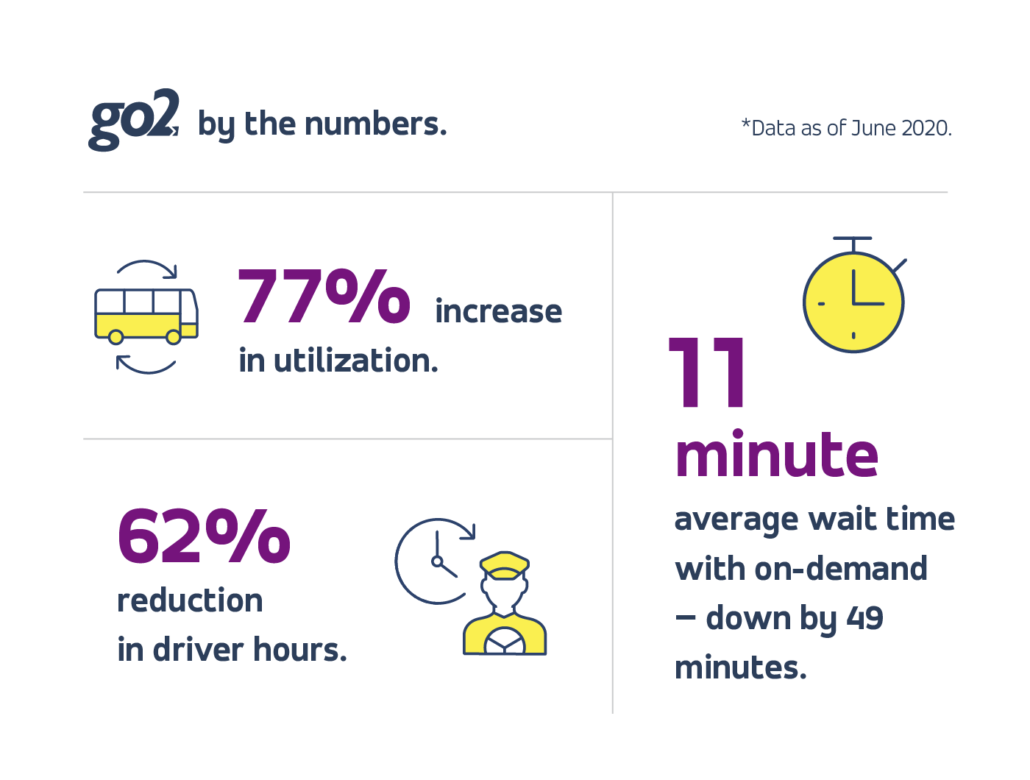

A good example of this is Go-Coach, a local bus operator in Sevenoaks, Kent, which replaced seven fixed route services with demand-responsive buses during the COVID-19 lockdown, and was able to serve the same level of demand and increase vehicle utilisation despite driving half as many miles. Passengers enjoyed lower wait times, too. By switching routes to DRT, they were able to actually improve quality of service while reducing expenses.

Transport leaders should be asking themselves: what’s the true cost of not providing sufficient transportation in my community? While traditional fixed route transport plays a critical role in providing mobility solutions, many residents do not live or work within walking distance of the nearest rail or bus station. As a result, those who own private vehicles will drive themselves, while those who cannot afford private vehicles — especially individuals in remote rural areas — struggle to access healthcare, jobs, community resources, and social connections.

Indeed, when we think holistically, we see that DRT systems initially dismissed as ‘unprofitable’ can create much more efficient public services in general. Transport is critical to preventing unemployment, providing access to preventative healthcare, and avoiding the social isolation that can lead to expensive care needs over time.

MYTH: There are so many DRT attempts that failed. Why would this be any different?

Reality: When DRT is put in place to address a real transportation challenge — and not just for innovation’s sake — it has proven very successful in the UK.

The path of progress is rarely smooth, and it is easy to point to a number of DRT schemes that have not survived (with the names Chariot, Bridj and Slide frequently referenced). If you look at each finished scheme, they tend to fall into one of three buckets:

- They weren’t solving a real problem for consumers. It is true for any product or service: in order to succeed, it must fill a gap in the needs of its target market. It is not unreasonable to ask whether the centre of London needed a new fixed route bus service when Chariot launched (even if it was booked via an app).

- They weren’t set up to succeed. In advance of launching any scheme, it is vital to its longevity that a clear set of success metrics are agreed by all stakeholders.

- The scheme does meet a real need, but is poorly executed. DRT is an umbrella term that now covers a very broad and expanding set of schemes and technology. Inevitably, they bring a variety of capabilities and levels of quality — there are some very good schemes out there, and there are some that are not delivering a compelling service to the communities they serve.

To illustrate, Transport for New South Wales ran a trial with dozens of different operators and tech providers and found that the tech provider makes a big difference. The two projects using Via technology (Northern Beaches and Macquarie Park) outperformed the others in terms of ridership growth by more than 100% over the course of the trial.

While some providers have hired a team of a few engineers to pull together relatively simple technology, Via has a global team of 300+ engineers with experience operating DRT services around the world. The engineering team — and the partner city — benefit from aggregate learnings applied across services over years of operation.

MYTH: DRT isn't new — you've just stuck an app on it. If it hasn’t gotten traction before, why should it now?

Reality: While DRT is not new to the UK, advances in both technology and consumer expectations — not to mention the highly variable demand patterns resulting from the COVID-19 crisis — give it renewed relevance today.

The basics of demand responsive transport have indeed been around for many decades , but these have largely been limited to “dial a ride” and community transport services targeted at older riders and other small-scale services. In the meantime, the delivery of DRT — and, indeed the context around — it have changed vastly. The oft-made argument that “It didn’t work in the past, so it won’t work now ” is an obvious thing to say, but it ignores the impact of societal innovation:

- Technology has changed. Earlier incarnations of DRT were technology-light, often with highly-manual scheduling and operating systems making them costly to run. They also sat entirely in isolation from the rest of the public transport network with no integration into it. Today, it’s possible to automate virtually all of DRT scheduling and planning processes. This unlocks better advanced planning, greater routing efficiencies, and much simpler back-office management; it’s not just about a front-facing rider app.

- Consumer expectations have changed. At a time where creating compelling alternatives to the private car is so important, delivering services in ways that consumers both expect and love is vital, both to retain existing customers and to attract new riders. If public transport does not deliver on the same level of experience as people now expect in other areas of their lives such as shopping and deliveries, it will only fall further behind.

- Demand levels have changed. Fixed route buses are the perfect solution for high volume, high predictability bus demand. The impact of COVID-19 has meant that, in large swathes of the UK, this is simply not the case. DRT can meet this new demand.

MYTH: People like the predictability of fixed route schedules. DRT is just the wrong solution.

Reality: Our experience around the world has demonstrated that well-run, well-scoped schemes are embraced by users of all ages and demographics.

We’ve worked with partners to introduce DRT systems in a range of settings, including replacing manually managed “dial a ride” services , replacing fixed route services, or adding a new public transport option on top existing services. In all cases, we work closely with partners to understand exactly what passengers will need in the service, adapting our technology to provide it.

When we’ve transitioned fixed bus routes to DRT services, we generally find that riders are happy to have a more convenient transport option than before. As passengers get used to a demand-responsive system, they learn quickly how long in advance they need to “order” their bus and, in any scaled scheme, find that the wait time will normally be very consistent day in day out. They also come to value very highly the flexibility and control it gives them. 80% of DRT passengers were not previously using public transport for their journeys, but had started doing so when a good DRT option was available. In many community transport services, riders rely on DRT systems to get them to and from medical appointments where it is crucial that they arrive and depart on time, and they can be nervous about a new solution when it first launches. Via riders have the option to book seats in advance by indicating whether they want to “depart at” or “arrive by” a specific time. This instills more trust in the system than a traditional bus timetable or old dial-a-ride service might do.

Beyond appealing to existing bus users, DRT also opens up bus travel to entirely new riders. A survey of ArrivaClick passengers showed that only 20% of customers previously took the bus. That means 80% of DRT passengers were not using public transport for their journeys, but had started doing so when a good DRT option was available. Since COVID-19 became a concern, passengers also often deeply value the guarantee of a safe, socially-distanced place to sit on the bus, with clear records of everyone else who traveled with them.

MYTH: App-based innovation risks leaving behind core users who don't have smartphones.

Reality: A sound technological platform ensures that anyone can take advantage of the system, including those without easy access to smartphones, the internet, or other technology.

It’s true: building a public transport system that solely relies on a smartphone won’t ensure its success. Cities today need systems that are built for flexibility and adaptability, so that operators can serve riders’ very local needs. In general, DRT systems today should have a variety of booking options to maximise accessibility for any type of rider:

- An intuitive, easy-to-use smartphone app for all passengers (or their carers) that includes inbuilt accessibility features like voiceover technology, adaptive font size, and enhanced contrast.

- A web portal for those who have internet access through a desktop computer.

- Telephone, SMS, or email booking.

When the London Borough of Sutton launched its new on-demand bus service, riders had the option of using the GoSutton app, logging into a GoSutton web portal, or calling in to a central booking line whenever they wanted to ride.

Passengers receive many modes of automated communication to stay up-to-date on their journeys, including in-app messaging, SMS, email, voicemails, phone-tree recordings, and even direct mailing, where appropriate. When operators use Via's technology to plan driver shifts and ride assignments, riders benefit from optimised grouping of passengers, efficient routing that minimise unneeded detours, and while operators enjoy much simpler back-office operations.

Now is the time.

It’s always easy to find a reason not to add technology to existing infrastructure, but when it comes to bus transport in the UK, the status quo just isn’t working. Many of the worries around DRT are rooted in myths and misconceptions that prevent us from making necessary progress. If we’re serious about connecting all households to the services they need, addressing COVID-19 challenges, mitigating climate change, and preventing massive congestion and pollution in our cities, now is the time for new ideas.