Whether the shockwaves of COVID-19 are behind us or just now being felt, the devastation will be with all of us for years. Like most industries, public transit has been hard hit — in some regions, ridership plummeted more than 90%. The world came undone so fast, and now agencies are relying on local, state, and federal funding more than ever before.

And that’s not the only bad news. Governments are also feeling the financial pinch, due to shrinking tax bases, reduced consumer spending, and increased demand for social services. Public transit — for many, the only affordable, reliable, and accessible way to get around — is a cornerstone of economic revival. Yet cities and transit agencies are now in the nearly impossible position of needing to prove its worth while their riders are nowhere to be found. In order to secure funding, continue operations, and bring cities back to life, transit agencies have an opportunity to think bigger by adopting a new Return On Investment (ROI) calculation — one that positions transportation not only as a worthwhile investment, but a foundational piece of a functioning society.

Re: ROI

For the true ROI to come into focus, we must look beyond the obvious farebox recovery ratio and measure a much broader net benefit of investing in transit. For example, when many people drive alone instead of taking the bus, society incurs significant, long term costs, not limited to:

- Countless miles of new highway construction

- Never ending road maintenance

- Significant and measurable environmental impacts

These costs are real, for local and federal governments that usually pick up a hefty tab, and for the communities that suffer from the impacts By using ROI, agencies can help our leaders quantify the positive impacts of and ultimately make the case for large-scale public transit investment.

$1 invested, $4 gained

There’s good news happening, too. The American Public Transportation Association (APTA) found that every dollar invested in public transit generates roughly $4 in returns. The study identified at least $232 billion in critical public transportation investments — largely focused on bus, light rail, and commuter rail projects in major urban centers and smaller cities. However, outside of these places, fixed-route transit options are often not efficient due to low population density and sky high private vehicle ownership.

This is where microtransit joins the conversation — it can deliver a similar positive ROI compared to traditional modes of public transit while still competing with private vehicles in terms of trip durations and ease-of-use. For example, Via’s West Sacramento microtransit service not only performs well on typical measures like farebox recovery ratio and cost per trip, but it also provides the broader benefits outlined in the APTA report that make transit such a compelling investment.

Microtransit benefits, let me count the ways

APTA’s methodology examines five factors: spending impacts, travel improvement impacts, access improvement impacts, non-monetary impacts, and other economic impact measures. Here’s how microtransit stacks up:

- Spending impacts are the benefits of direct and indirect spending required to provide public transportation. Like any other type of transit, microtransit requires drivers, maintenance, administrators, and manufacturing to function. Since drivers of microtransit services are typically residents of the area, there’s a high likelihood that their earnings are largely spent in the local community.

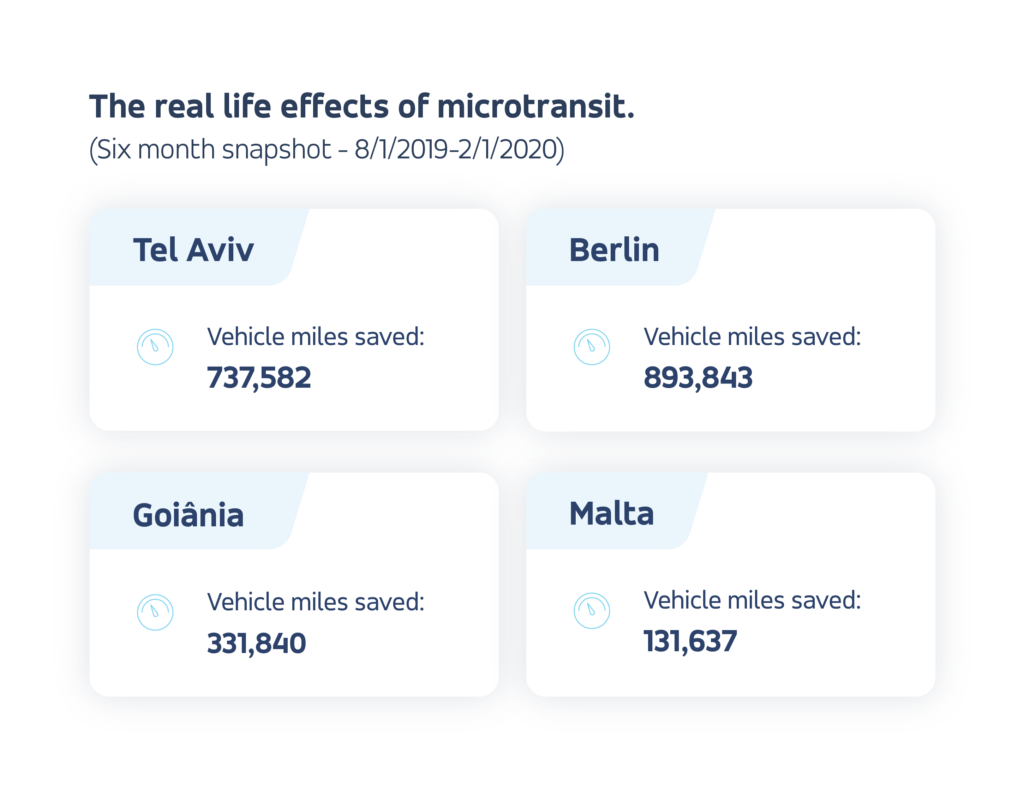

- Travel improvement impacts cover four categories: travel time savings, travel cost savings, reliability improvements, and safety improvements, all of which also apply to microtransit. In fact, microtransit services often have comparable travel times to private vehicles, even in areas where fixed-routes would typically only run infrequently. This means that travel time savings are often more pronounced than other forms of transit. Also, by efficiently grouping passengers together, microtransit reduces Vehicle Miles Travelled (VMT), which saves money, reduces congestion, and makes our roads safer. Even researchers at Boston Consulting Group say so: “By pooling passengers, on-demand transit services can go a long way toward reducing the number of vehicle miles traveled,” BCG wrote in its latest report. “In Arlington, for example, the service helped eliminate nearly 400,000 miles of travel that would have occurred if the passengers had driven solo, corresponding to a reduction of 36% of total vehicle miles traveled.”

- Access improvement impacts are productivity changes from expanded public transit service and reduced traffic congestion. Translation: businesses enjoy increased employee productivity and access to a broader, more diverse, and higher-skilled labor market. Again, microtransit excels in this regard, as most microtransit services allow travel between thousands of virtual bus stops within a zone, meaning the number of jobs someone can access is significant when compared to a linear, fixed-route bus or train.

In the United States, even in metropolitan areas, fewer than 25% of low and middle-skill jobs are accessible by public transit in less than 90 minutes. According to West Sacramento Mayor Christopher Cabaldon, however, the city’s on-demand transit network is having a tremendous effect on access to jobs. “For seniors, it’s been a game changer. For teenagers — a game changer. For parents — a game changer. About 40% of youth say they are working now and could not have had a job without this service. It’s also cheaper for us. Per ride, it’s dramatically less expensive than the transit system. So a pretty powerful innovation.” - Non-monetary impacts measure factors such as environmental benefit. Like any form of public transportation, the environmental impacts are dependent on the exact operating model and context. However, microtransit services typically use smaller, cleaner vehicles with lower carbon emissions per passenger mile than private vehicles, and in some cases, lower than certain bus routes. Around the world, these investments in new forms of on-demand shared public transportation are dramatically reducing congestion and the volume of vehicles on the road.

- Finally, there are several other economic impact benefits related to land development, parking lot construction, and property values. For example, with parking lots in some regions costing more $70,000 per space, first-and-last mile microtransit services can help to reduce real estate construction costs by limiting demand for parking at transit hubs. The Seattle metropolitan area presents one such example where a service launched last year by King County Metro and Sound Transit — called Via to Transit — has improved station access, reduced congestion, and is reducing the need to build expensive, wasteful parking lots.

COVID-19 is still with us. Funding is scarce. And public transportation may be in the fight of its life. Transit agencies can help themselves by demonstrating how their ROI reaches far beyond the farebox recovery ratio. Like all forms of transit, microtransit will play a powerful role in helping cash-strapped public transit agencies recover from our global crisis and provide efficient, affordable, and sustainable transportation for decades to come.