As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to upend public transport as we once knew it, we’ve seen plenty of news about the efforts underway to prevent a mass return to private cars once people begin to move around again. We’re particularly heartened by the amount of momentum we’re seeing in the rural transport space — especially given how rural communities have been cut off from access to public transport for years. Between the Department for Transport’s call for evidence on Rural Mobility and the Scottish MaaS Investment Fund, the time has never been better to consider innovative approaches to network recovery.

Rural transport in crisis.

Bus networks have always been the centrepoint of rural transportation, but are inherently challenging to deliver due to their lower passenger densities. Decades of funding cuts have left rural communities with increasingly limited bus networks, creating a negative downward spiral in transport access. In many areas, a bus will now stop only once or twice per day, and it will then take a slow and meandering journey through many rural hamlets before reaching the train stations, shopping centres, or healthcare providers passengers need to access. It’s no wonder that many people turn to private car journeys for a much more efficient and reliable experience.

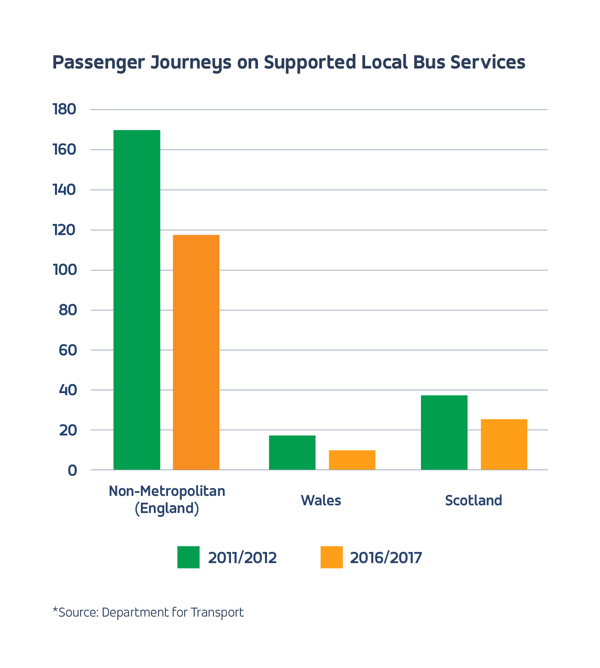

As a result, bus patronage and ridership in non-urban areas has dropped by as much as a third in England, with drops in Wales and Scotland as well. As fewer people use buses, revenue for operators drops, and councils may trim funding further, causing service reductions that make public transport even less attractive.

A disproportionate impact.

A disproportionate impact.

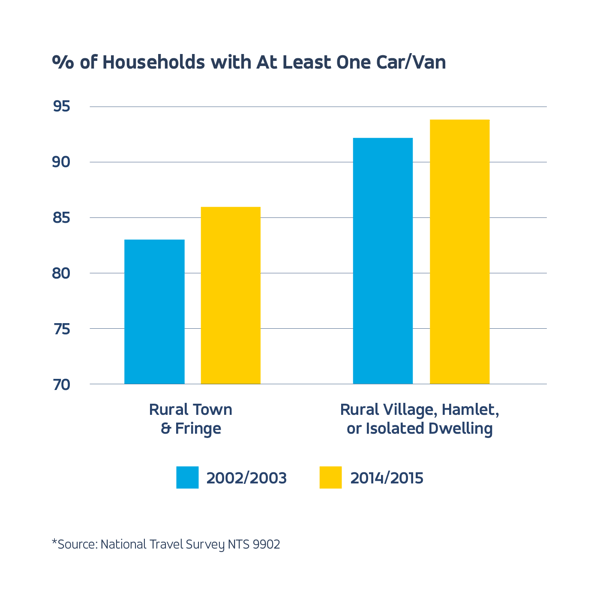

This widening gap in rural mobility provision means that the roughly 18 percent of the UK population who live in rural communities are increasingly cut off from employment, social interaction, access to services, and more unless they have private car access. Further, the lack of shared transport options has serious implications for our ability to meet climate change and sustainability goals.

This isolation comes at a social and economic cost.

- Economic opportunity: Research shows that when individuals do not have reliable, affordable transport options, their access to the jobs market and training opportunities is artificially limited. That means that rural families are essentially forced into car ownership in order to find work or education outside of their very immediate vicinity, and that the UK has foregone the potential economic contributions these communities might have made if they could access appropriate jobs. These types of challenges have been especially acute for young people, and are one reason many young workers and families have left rural areas.

- Access to services: Reliable transport is vital for access to healthcare, shops, and services, especially as rural populations tend to be older. Indeed, residents of rural communities may not schedule the medical appointments they need because they cannot travel to hospitals or doctors, potentially leading to delays in care. There’s a higher potential for missed appointments due to unreliable or delayed transport, wasting limited NHS resources.

- Social isolation: It’s equally easy for individuals within these communities to become socially isolated and disconnected. As the nation has learned all too well over this prolonged period of lockdown, social interaction matters for health and well-being. Without the ability to affordably and reliably meet up with friends and family, rural denizens — especially older ones — see their quality of life reduced, and may become more likely to need expensive social care over time.

- Sustainability and climate change: Hundreds of councils across the UK have declared a climate emergency, and should in theory be doing everything possible to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate the effects of climate change. Today, about a third of the UK’s carbon emissions are associated with transport, primarily from road travel. Any serious attempt at reducing emissions must include a concerted effort to take people out of private cars and into more sustainable shared options. Yet these communities are actually increasing their rates of car ownership.

What can be done.

What can be done.

The pandemic has brought the UK to an inflection point for rural transport. One very possible outcome is a further worsening of the status quo — a continued underinvestment in chronically insufficient rural transport systems, essentially requiring that rural households use a private car or stay home. Without the right incentives or support, commercial operators will likely double down on their most commercial, often urbanised routes in an effort to financially survive the pandemic. Councils, faced with their own funding crisis, could be forced to reduce already dwindling spends on supported bus services.

This potential failure to preserve rural public transport would mean deprioritising climate goals, allowing social and economic costs to spiral, and simply accepting that some communities will be left behind. An alternative path forward is to use this crisis as an opportunity to ‘build back better’ and invest in the transport systems we’ve long needed to help rural communities thrive through proven technological solutions. These will vary across communities, and it is worth exploring several ideas in parallel to see what will work for each hamlet, village, and town.

There is no single panacea, but tech-enabled demand-responsive transport (DRT) can certainly serve as a starting point for many communities. Whilst DRT is not a new concept, advances in both technology and consumer expectations as well as highly fluctuating demand patterns resulting from the COVID-19 crisis give it renewed relevance and importance. DRT systems allow operators to more efficiently meet low and inconsistent demand. Rather than running fixed route buses regardless of passenger numbers, a DRT service ensures that supply is entirely matched to demand. For bus passengers, it can be transformative. Where previously they had to fit their schedules around bus times, the reverse can now be the case allowing them to more fully and reliably access jobs and services.

Tees Valley recently launched a DRT service that gives rural and suburban users the ease and convenience of a private taxi, but uses affordable and sustainable shared minibuses. The community went from having zero bus provision to being able to book a ride and enjoy a wait time of only 20 minutes, on average, for a bus to arrive.

Even before the crisis, the government seemed like it was taking the right steps toward reinvesting in rural public transport. The Department for Transport’s Rural Mobility Fund will support projects in England that aim to improve rural transport provision, and Scotland’s MaaS Investment Fund is likely to address a range of issues for more isolated communities. These are promising initial signs — the key question, however, is whether we will follow through on these promises and accelerate and expand transport investment to enable the innovation we’ll need to get out of this crisis.

We have an opportunity to reopen the UK in a way that will let us be better connected, more equitable, and more sustainable than before. Let’s not waste it.