While sheltering in place is reducing the spread of COVID-19, it's also having another positive unintended consequence: traffic congestion and emissions are plummeting around the world. In China, the economic slowdown has caused a stunning 25% reduction in the country’s emissions. In normally gridlocked cities like New York, traffic speeds are up by as much as 288%.

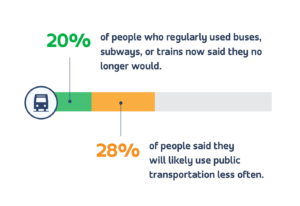

The turn of events has transit and urban planning experts wondering how to sustain the momentum as cities return back to normalcy. A study by IBM, however, confirms that the road ahead may be difficult as people flock to personal vehicles rather than return to public transportation. The study shows that more than 20% of people who regularly used buses, subways, or trains now said they no longer would, and another 28% said they will likely use public transportation less often.

Those fears could open the floodgates for commuters. A new study from Vanderbilt University projects a dramatic rise in traffic across the United States caused by a rush to single-occupancy vehicles after the shutdown lifts, specifically hitting the area in and around San Francisco, California the hardest. The trend could potentially increase morning commutes by up to 42 minutes. Vanderbilt University's model projected that in San Francisco, the increase in congestion is projected to add an additional 556,000–2,736,000 traffic hours per day spent commuting, or 20–80 minutes per person round trip. New York and Los Angeles are expected to be the second and third worst-hit areas in the US, respectively.

Those fears could open the floodgates for commuters. A new study from Vanderbilt University projects a dramatic rise in traffic across the United States caused by a rush to single-occupancy vehicles after the shutdown lifts, specifically hitting the area in and around San Francisco, California the hardest. The trend could potentially increase morning commutes by up to 42 minutes. Vanderbilt University's model projected that in San Francisco, the increase in congestion is projected to add an additional 556,000–2,736,000 traffic hours per day spent commuting, or 20–80 minutes per person round trip. New York and Los Angeles are expected to be the second and third worst-hit areas in the US, respectively.

Given that traffic congestion in 2018 equated to roughly $87B in lost productivity in the U.S. alone, both the global economy and individual employers have a vested interest in ensuring that we don’t take a step backward in these efforts.

Given that traffic congestion in 2018 equated to roughly $87B in lost productivity in the U.S. alone, both the global economy and individual employers have a vested interest in ensuring that we don’t take a step backward in these efforts.

The daily commute could be a nail in the coffin of recent transportation progress — not an easy pill to swallow for transit authorities and operators. But, there’s still hope. Anxieties over commuters leaving public transportation for good has many transit leaders willing to bet on big changes to their networks. In particular, they’re choosing new technology that's been proven to win-over drivers and pull them out of private vehicles: on-demand microtransit.

Congestion will still be a problem. On-demand public transit could still be the answer.

Prior to the pandemic, cities were onto something that could help them from bouncing back to gridlock: on-demand microtransit technology, sometimes even applied to existing fixed-route bus networks. In practice, microtransit blends the best of mass transit with ride hailing services, attracting new riders to public transportation.

For example, in West Sacramento, California, a survey revealed that 49% of riders would have hailed a private Uber or Lyft if the city didn’t have its local shared microtransit service. Moreover, 31% said they would have driven their personal vehicle over using the local service. That means that well over half of riders preferred to use the shared microtransit service, Via West Sacramento, over ride-hailing apps and their personal vehicles. This is not limited to the US, either. In a similar survey conducted with microtransit riders in Tel Aviv, Israel, and Sutton, United Kingdom, riders shared that while they used their private vehicles about a third of the time they needed to get somewhere, they used public transit and shared microtransit nearly 2/3 of the time.

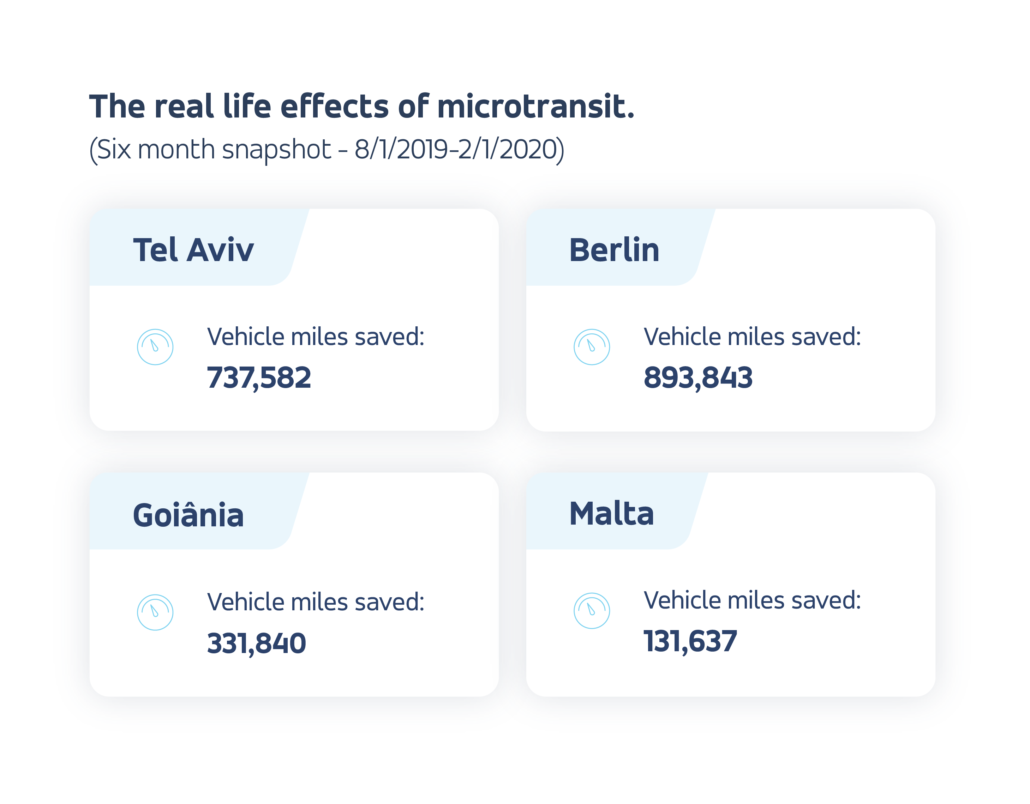

Around the world, these investments in new forms of on-demand shared public transportation are dramatically reducing congestion and the volume of vehicles on the road.

These significant savings also equate to a profound reduction in the amount of carbon emissions created by single-occupancy vehicles. When riders have access to reliable public mobility, it can help increase economic mobility, congestion, and their overall carbon footprint.

A study by Boston Consulting Group found that, when compared to fixed-route mass transit, microtransit’s convenience and flexibility both reduces congestion and brings good jobs within reach of neighborhoods poorly served by the status quo. By increasing economic mobility, residents in the wealthiest 10% of neighborhoods have access to three times more qualified jobs via public transit than residents in the bottom 50% of neighborhoods.

Before the pandemic microtransit was also helping reduce carbon emissions – it still can.

Although the world was already making small advancements in reducing extremely high carbon emissions, the coronavirus has sped up that progress. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the world will use 6% less carbon in 2020 – which is the equivalent to a reduction the size of energy demand in India.

In large part, that progress can be attributed to lockdowns and significant reductions in travel across the globe. As shelter-in-place orders are lifted and people return to work, however, the world will slowly go back to being mobile again. And there are still ways cities and transit operators can help continue to make additional progress in lowering overall carbon emissions, as they were starting to do before the pandemic as well.

While the world returns to a place where mobility and travel are necessary, continuing to move ahead with new forms of shared transportation like on-demand microtransit technology will be a way forward in helping get people back to work, and back to a world where we’re all trying to reduce our carbon footprints.

%206.png?width=71&height=47&name=The%20Buzz%20Blog%20Hero%20(1750%20x%201200%20px)%206.png)