In the spring of 2019, Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop knew he had a problem. Bus route cuts in Greenville, a neighborhood to the south of downtown, brought the longstanding issue of transit access in outlying Jersey City neighborhoods to a crisis. Largely communities of color, these areas saw their affordable transit options dwindle.

It was the kind of inequity frustratingly common in many of America’s cities: the New York subway offers easy access to nearly every part of Manhattan, but try traveling from Brooklyn to Queens. In response, Mayor Fulop took an outside-the-box look at the long-standing systemic issue of transit inequities that often disproportionately affect minority and low-income urban communities. Rather than continue fruitless appeals to the state’s transit agency for better bus routes, he tasked his team with exploring what kind of transit options the City could administer directly.

Though tech-enabled microtransit came quickly to mind, services on the scale the City contemplated were at that time operational in only a few locations in the United States — and it was not obvious that these services, in places like Arlington, Texas, and West Sacramento, California, would translate well to a more urbanized city with relatively denser fixed-route transit coverage. Would microtransit cannibalize existing public transit, drawing affluent riders off the PATH, Jersey City’s subway system, rather than filling transit gaps in Greenville? Would vans spend their time stuck in traffic, contributing to congestion and pollution?

Via Jersey City launched in March 2020 as a part of the public transit system, costing just $2 per ride for most trips. Now, nearly two years later, the success of the service — its resilience and growth during the COVID-19 pandemic , and its impact on riders who identify as people of color — is clear. A success story for Mayor Fulop, the service is also a blueprint for deploying microtransit as public transit in a complex, diverse urban environment, with clear lessons to offer cities around the country, especially those struggling with lower transit ridership and bus cuts since the onset of COVID-19. Two years of TransitTech in Jersey City have yielded four main insights that will be critical as cities and transit agencies look to rebound in 2022.

1. Public transit ridership can still grow, even during COVID.

The pandemic has had a disastrous impact on public transit nationwide, as ridership plummeted precipitously with lockdowns and the roads refilled with private cars when restrictions eased. National bus ridership is still at ~55% of what it was in 2019, which itself was part of a long, but slower, slide in ridership that began in 2012. Fixed route ridership on New Jersey Transit was down 23% in 2020 compared to 2019, according to the latest available NTD data.

But apart from an early dip in April 2020, Jersey City’s microtransit service has grown steadily, with monthly ridership in December 2020 double that at launch (~26,000 compared with ~13,000), despite record-high coronavirus cases. With the addition of Saturday service and continued economic recovery, by December 2021 monthly ridership had nearly doubled again to ~48,000. These numbers suggest that, despite the current crisis and long-standing trends, there is still room for public transit to grow.

2. Careful service design can mean a microtransit service complements, rather than cannibalizes, existing public transit.

In a city run entirely on microtransit, every new ride signals a trip that wasn’t taken in a private car. But if a Jersey City resident who might have taken the PATH from Newport to Grove Street simply takes Via Jersey City instead, microtransit is not doing its job of extending access to public transit as intended.

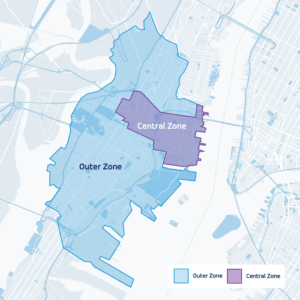

To avoid cannibalizing existing services in transit-dense downtown, Via Jersey City’s booking engine prevents trips that take place entirely within this “inner” zone. The result is a ridership pattern that flows between outlying neighborhoods and downtown, filling the gaps left behind by canceled bus routes. Moreover, 45% of all trips begin or end at a transit hub, suggesting that the service is actually driving ridership to fixed route transit. Indeed, the Via Jersey City team is considering introducing information about fixed route service directly within the booking app to drive even more ridership to fixed route transit options.

3. Tech-enabled transit can be just as accessible as traditional public transit.

City officials often fear that tech-enabled microtransit will be as exclusionary as some single-occupancy, app-based ride hail services that are expensive, inaccessible to riders with disabilities, and impossible to book without a smartphone and a bank account.

But with its low fares, wheelchair accessible vehicles, and phone-booking option, Jersey City’s microtransit service has attracted a diverse ridership .

But with its low fares, wheelchair accessible vehicles, and phone-booking option, Jersey City’s microtransit service has attracted a diverse ridership .

- 51% of riders report an annual household income of less than $50k, with 28% making under $25k.

- 88% of riders identify as people of color.

In short, microtransit in Jersey City is as diverse as the neighborhoods it was built to serve: in Greenville, for example , 82% of residents identify as non-white and 33% report an income under $25k.

4. Creative, proactive funding and revenue strategy can deliver long-term financial sustainability.

Very few public transit networks in the United States recoup their costs through farebox revenue, instead relying on federal, state, and local funding options. This money has been shown to be a good investment: in a recent study, APTA estimates that every $1 spent on transportation yields $5 in economic returns.

Nevertheless, with limited traditional, non-competitive funding options available, cities and transit agencies have begun to develop alternative strategies for the long-term sustainability of their services. In Jersey City, advertising in and on the vehicles, in the form of roof “toppers” and in-vehicle screens, has become a significant and steady source of additional revenue that can fund additional vehicles and service hours as needed. The City and Via collaborate to identify and pursue competitive grants to ensure no eligible money is left behind. With the recent passage of the bipartisan infrastructure bill, opportunities for these kinds of funds will only increase.

Looking forward.

Only two years after launch, the landscape for on-demand microtransit looks very different. The mode has exploded worldwide, with hundreds of services launched in 2021 alone. Perception of microtransit as a viable component of a transit network — one that transit planners and consultants now regularly include in network redesign projects — is, in part, the result of the encouraging data coming out of places like Jersey City. The City has been a strong leader through a very difficult time in public transportation. Let’s see what Year 3 will bring!