Need a primer on some of the terms used below? Check out our new glossary for all of the TransitTech definitions you could ever need — and then some.

When Amazon introduced its Prime subscription service back in 2005, it took a sledgehammer to everything we thought we knew about retail. Costco is now famous for the cult-favorite $1.50 hot dog and soda combo — a deal so cheap, it’s practically impossible to resist.

And then there’s the buy one, get one free or ‘BOGO’ approach, a sales offer so easily-implemented that everyone from McDonald’s to Amtrak is running one. But what you might not realize is that these classic promotions don’t only have to apply to food and retail. Taking inspiration from these innovative spaces may also be relevant for public transit.

With an on-demand transit service (or microtransit), cities and transit agencies have all of the tools necessary to implement sophisticated, dynamic pricing structures that drive up ridership numbers and bring in more net profit — usually, by strategically lowering fares. Charging lower rates than your gut may tell you — and, in some instances, giving away rides for free — actually drives revenue and ridership over time.

This idea isn’t just theoretical; we have the proof. Just look at data from a few of our on-demand services in Texas, California, and the United Kingdom.

Subscriptions — they’re not just for streaming.

Keeping users coming back is key and rider loyalty is what makes a service soar. Subscription models demonstrably improve acceptance, completion, and engagement rates, and also compensate for those unavoidable periods of lower-than-ideal service quality — nobody’s getting too upset over longer wait times when they feel they’re getting a great deal. And in addition to increasing service loyalty, subscription models can actually boost revenue and hook already-engaged riders for the long term.

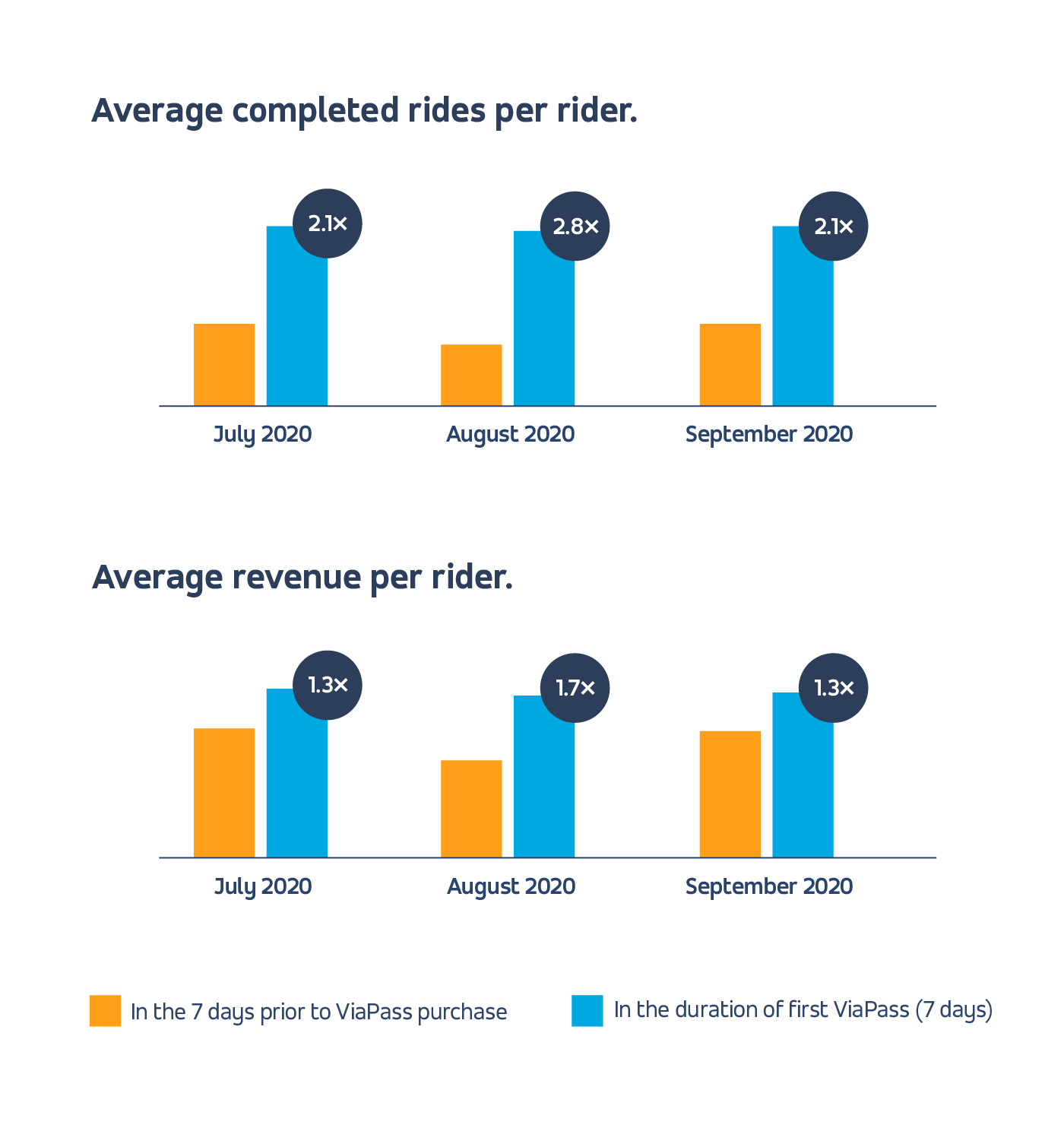

These subscriptions can be fully customized, too: Operators can work with their tech provider to not only adjust the discount itself, but also limit discounts to certain geographic areas, times of day or days of the week, promotional codes, or more complex filters tailored to their riders’ particular needs and behavior. In Arlington, Texas, Via’s microtransit solution replaced the single-route bus service and expanded coverage to previously unconnected areas of the city. Each ride within the service zone costs $3 but, for $15, residents can purchase a weekly ViaPass.* ViaPass holders can book four shared rides per day anywhere within the service zone, for seven days at a time. The massive cost incentive here — bringing an $84 value down to the price of a takeout meal or two — has clear benefits for riders, yet might seem like a questionable financial decision for cities and operators. But turns out, what’s good for the rider is also good for business. Data shows that Arlington passholders ride up to 2.8X more in the week after purchasing a pass than in the week before purchasing. Further, each passholder brings in up to 1.7X the revenue in that first week than they had the week before. It’s clear that, though operators are providing a “discount” on each ride, it’s in exchange for increased ridership, loyalty, and engagement with the on-demand service. In fact, passholders can ultimately contribute to the service’s total overall revenue at higher margins than those who pay full price for each ride, due to the cost of the pass being more than what they would previously spend in a given period on ride fares, passholders exceeding their daily ride maximum, or passholders riding with +1s who are paying full price.

And now, a lesson from Costco.

Let’s zoom in on a rather inconspicuous part of the third-largest retailer in the world: that notorious $1.50 hot dog and soda combo deal. The idea of pricing something so outrageously low that it becomes wildly popular can actually apply to on-demand transit fares, too.

To see this in action, we’re turning to Los Angeles and Via’s partnership with the Los Angeles Metropolitan Authority (LA Metro). The LA Metro service provides first-and-last mile rides, connecting Angelenos to three major transit hubs in the city. The challenge here was to drive growth with minimal marketing spend. The proposed solution? Simply test aggressive pricing discounts.

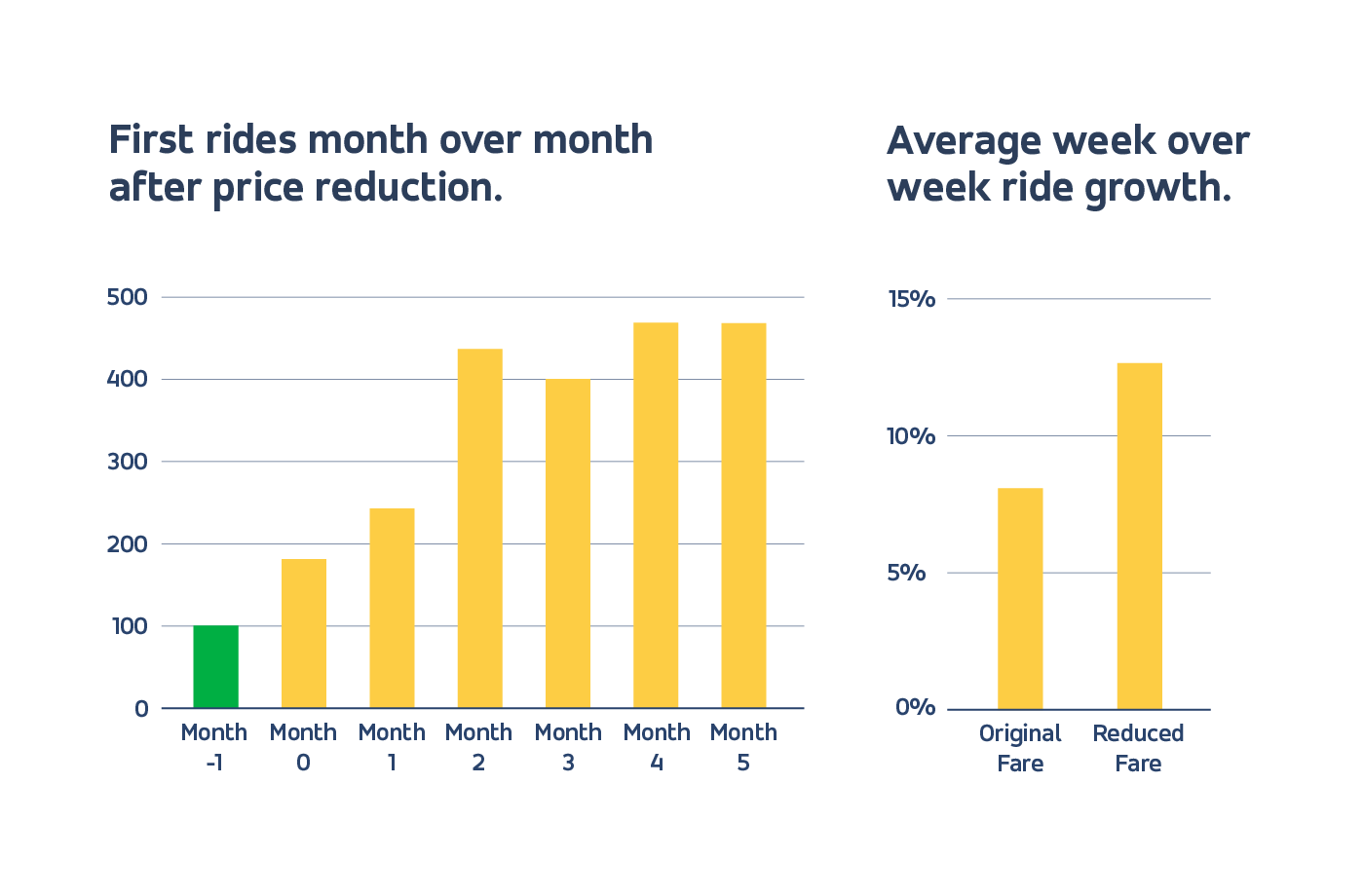

Again, this probably isn’t what you might think of as a surefire way to sustain growth over time but, as we’re learning, unconventional pricing strategies can have unexpectedly positive results. In fact, low fares in LA increased new ridership both immediately and well after the change took place, thanks to referrals and the virality that comes with a great deal. The graphs below show the increase in rider acquisition and engagement as a result of a $1 decrease in ride fares. Not only did new rides increase over several months after the fare reduction, but overall weekly ride growth for both new and existing riders saw a marked acceleration.

The power of a +1.

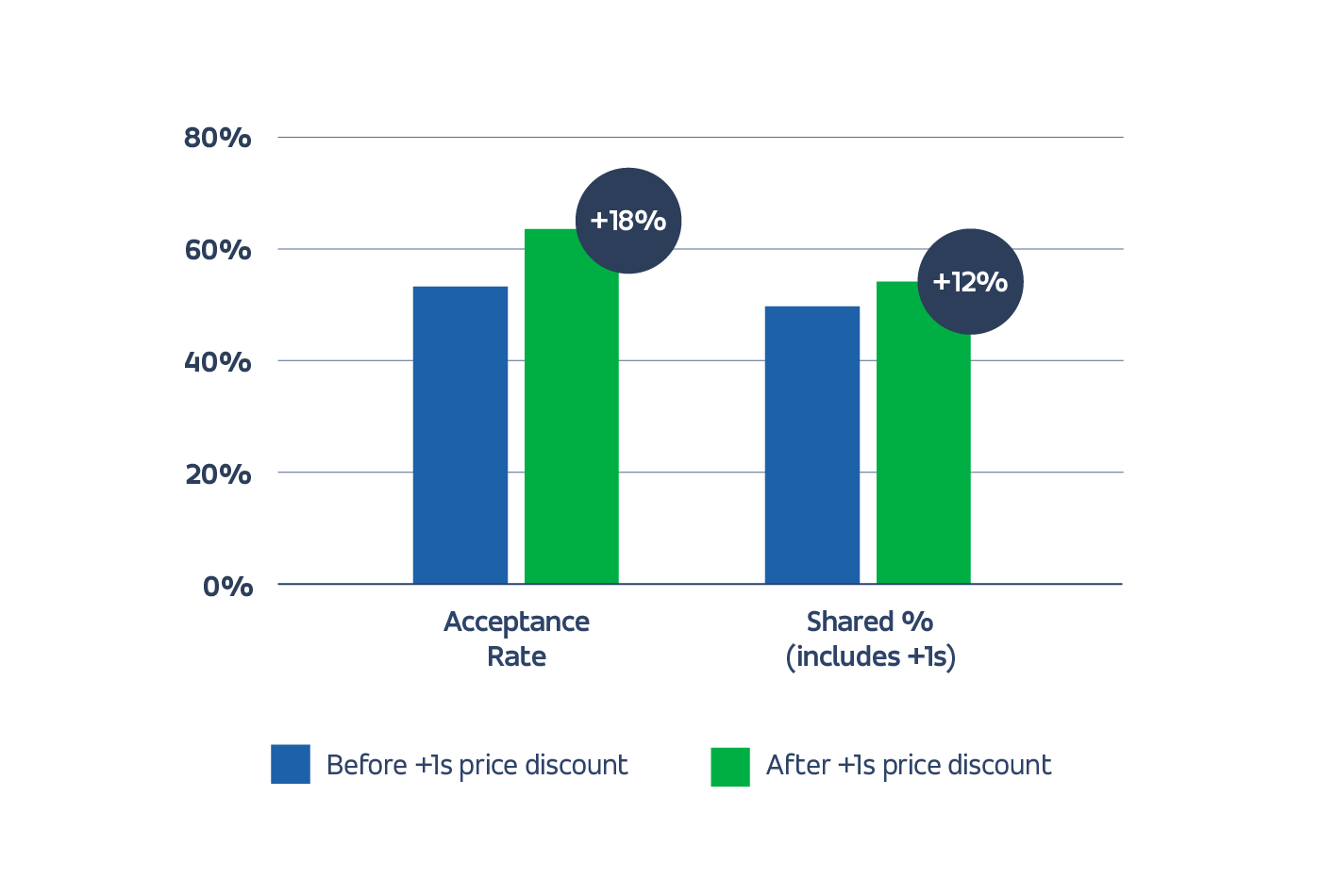

Plus ones are powerful — and our operation in the United Kingdom proves it. Together with our transit partner, we launched a large-scale urban deployment offering shared, on-demand transportation. The goal was to increase utilization, thus decreasing the cost per ride on the operations side, without changing the core pricing structure of the service. That’s where +1 pricing comes in.

When operating larger 13-15 passenger vans, as this deployment does, you can generally count on at least one seat being available at any given time. This means that, whenever a rider books an on-demand trip, there’s zero cost involved in serving one additional rider at the same time — the +1 can simply fill one of the empty seats in the vehicle.

What we’re doing here is both maximizing the utility of large vehicles that would otherwise drive around with empty seats, while also incentivizing multi-passenger booking through attractive and transparent pricing. The prospect of bringing a friend along for cheap gives a user one more reason to book with the on-demand service and encourages larger groups to accept offers more often, increasing the number of shared rides across the whole service.

So, the team gave it a shot: Decreasing the price of +1s to just £1 each, and enjoying a boost in ride volume and shared ride frequency as a result.

The lesson we can learn from this experience in the UK is that most services aren’t seat-constrained in their early growth stages and, when this is the case, an additional rider (or two!) per booking has a low marginal cost-to-serve. And +1 pricing can come with some exciting indirect benefits as well — exposing more people to your service through friends of users, and generating word-of-mouth buzz.

The lesson we can learn from this experience in the UK is that most services aren’t seat-constrained in their early growth stages and, when this is the case, an additional rider (or two!) per booking has a low marginal cost-to-serve. And +1 pricing can come with some exciting indirect benefits as well — exposing more people to your service through friends of users, and generating word-of-mouth buzz.

The takeaway.

So, despite popular belief, sometimes ultra-inexpensive (or even free) rides is the ticket to success in transit. But this is just a starting point. With any on-demand service, transportation leaders and their TransitTech partners are empowered to design their own pricing strategies that work for their particular ridership, with dynamic structures that are mutually beneficial for the agency’s bottom line and the rider’s needs.

We’re all too aware that bringing in revenue will be a key goal for many transit agencies post-COVID. While the focus right now is and should be on transporting individuals safely in the midst of the pandemic, the transportation industry’s survival will necessitate rethinking the elements of running a service that we’ve previously allowed to run on autopilot. Together, we can create a more sustainable future for transit.

*Note: In January 2021, Via Arlington expanded its service area to cover the entire city. As a result, new pricing goes into effect on February 15, 2021.

This article is a part of our Clarifying the Counterintuitive series, where we use real data from Via’s existing partnerships to prove why the seemingly obvious path forward might not always equate to a successful service model.