By now it is no secret that COVID-19 has decimated the public transit sector. Ridership on public transportation is down by 63% in the United States compared to pre-crisis levels, according to a recent study of passenger movements by Transit, the multimodal trip planning app.

While the coronavirus lockdowns have cut personal travel across many transportation modes across the globe, US transit agencies are uniquely vulnerable — and they need to do something fast. Some experts say reforming public transit is the golden ticket to reviving the economy.

If so, we have plenty of work ahead of us. Unlike other highly developed industrialized countries, the US has seen a decline in overall public transit ridership in nearly all cities since at least 2015. This ridership decline has struck bus services the most severely, with cities such as Los Angeles and Miami showing 10-year drops of between 20-30% even before the crisis. A slew of factors — from cheap auto loans and fuel prices to gentrification and the suburbanization of poverty — were likely driving the bus ridership decline before the crisis hit. In 2019, bus systems served their lowest ridership levels since the 1970s, with 2020 almost certain to mark a new low.

During the COVID recovery, transit agencies will have their hands full simply trying to recover the riders they move by rail in the densest markets, like New York, Chicago, Boston, and San Francisco. But the challenge of regaining bus ridership will be an order of magnitude greater, particularly for smaller and mid-sized transit agencies that only operate bus services.

The cost to keep America moving.

Transit agencies are already anticipating enormous deficits, which will force them to ultimately cut service and accumulate unprecedented levels of debt. The research organization Transit Center estimates that the public transit industry will lose between $26 billion and $40 billion in revenues by the end of 2020 as a result of COVID-19. The federal CARES Act, which delivered $25 billion to transit agencies, is unfortunately only a temporary stopgap measure that cannot fully restore agencies’ financial health.

In April, Transit Center estimated that the New York MTA, responsible for 38% of the nation’s transit ridership, will face an annual shortfall of between $4 billion and $8 billion, even after taking the CARES Act into account. BART faces an annual shortfall of $258 million to $452 million due to COVID-19, while the entire San Francisco Bay Area and its 27 transit agencies received just $822 million from the CARES Act. The coronavirus has created systemic challenges to transit ridership that will last far longer than these bailout funds allow.

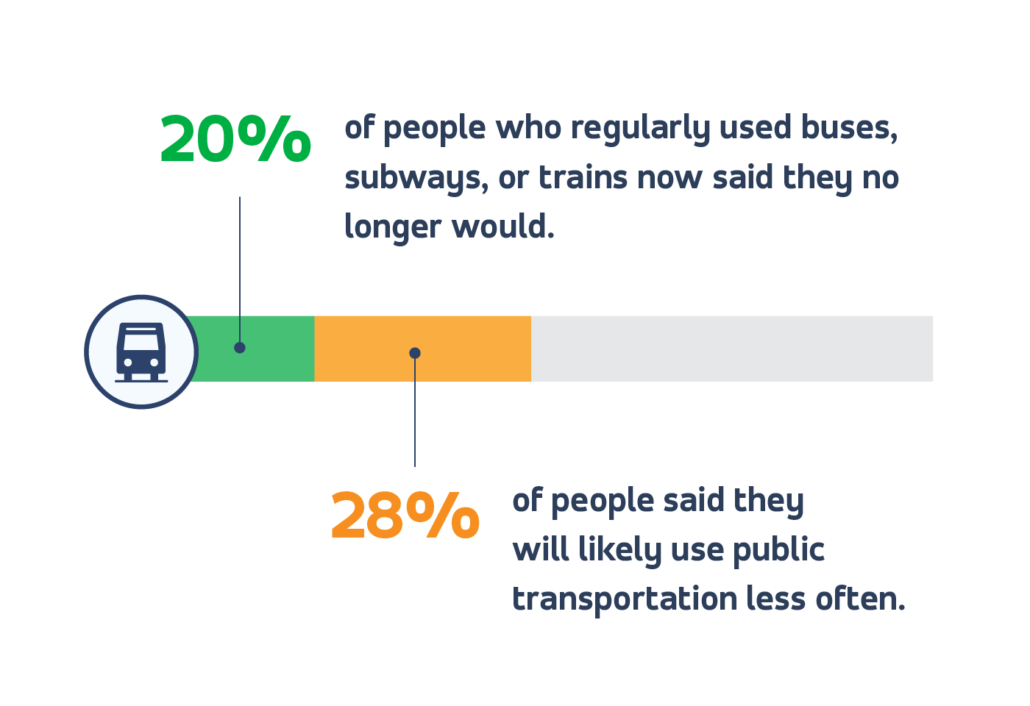

Even once statewide lockdowns have officially eased, many current riders are likely to abandon transit for the foreseeable future. In a recent survey conducted by IBM, half of all respondents said they would use transit less or stop using it altogether. These changes will drastically worsen the traffic conditions in which bus networks operate, eroding bus services’ reliability and on-time performance.

A new traffic calculator from Vanderbilt University finds that if even one in four current transit commuters switches to driving in a single occupancy vehicle — a best-case scenario, and one that nearly matches the likely modal shift IBM predicted in its survey above — one-way travel times will increase in most major cities by 5-10 minutes per day, with the highest increases projected for the San Francisco Bay Area and New York metropolitan areas which already had stifling congestion before COVID-19.

Are we headed toward a ‘transit death spiral’?

Worsening traffic congestion will lead to worsening on-time performance and reliability for bus systems, which will magnify their ridership losses due to their pre-existing challenges in retaining riders as well as COVID-19-related health concerns. Shrinking ridership will reduce fare revenue for transit agencies, which will be forced to cut service hours, defer maintenance and capital projects, and accumulate higher debt levels to maintain the service that continues.

These service cuts will mean lower-quality service that many of today’s riders will seek to avoid: longer wait times for slower, less reliable service in more congested conditions, which will induce further ridership losses. In transit industry circles, this negative feedback loop is known as the “ transit death spiral,” one that was already in effect even before the crisis in many cities. Sadly, the first cycle of transit service cuts is already underway in the nation’s largest transit markets, including New York City and San Francisco.

The severity and longevity of these service cuts will hit some agencies harder than others. In the near-term, the worst-affected agencies will be those located in states and cities where lockdowns have been most strict, and in effect the longest, such as those in New York, California, and Washington State. Agencies that are most dependent upon fare revenues to support their operations — with a high farebox recovery ratio — will also be heavily impacted, an ironic twist given that a high farebox recovery is typically the mark of a highly effective transit agency less reliant on external funding sources.

In the longer-term, however, other agencies will also be severely impacted as the economic toll of the crisis sets in. With little direct support from states or the federal government, many transit agencies depend on a combination of local sales, payroll, income, or property taxes to pay for operations. Each of these funding sources are likely to shrink as historic job losses accumulate and the real estate market cools. Bus service cuts will disproportionately affect lower-income Americans and communities of color, even at a moment when more than one third of transit riders are “essential workers.”

How deteriorating bus networks impact inequality.

The coming bus service collapse is likely to magnify the existing social injustices of American society. Bus service cuts will disproportionately affect lower-income Americans and communities of color, at a moment when more than one third of transit riders are “essential workers” who have risked their lives to provide us with the irreplaceable labor we depend on. The core of what we now call essential workers — primarily lower-income people, immigrants, and people of color working in healthcare, logistics, and the service-sector — are highly dependent on buses to get to work. Without access to fast, frequent, and reliable bus service, essential workers’ commutes and the lifesaving services they provide are in jeopardy. Previous crises have shown that transit agencies are more reluctant to reduce subway, commuter rail, and light rail services compared to bus service, meaning that buses — especially those serving lower-income corridors, lower-density areas, and communities of color — are likely to bear the brunt of the cuts.

This is partly because buses are a more flexible mode to operate than rail or subway services, with each bus trip cut from the schedule affecting at most, 50-60 riders, compared to the hundreds of riders affected by each train trip cut. But part of reducing service involves a political balancing act of distributing limited service hours across a segregated landscape, leaving more marginalized rider groups more likely to be affected by the service cuts. Buses have long served a lower-income ridership compared to rail. As bus service becomes increasingly infrequent and unreliable, middle-and higher-income riders (those more likely to have access to personal vehicles) are likely to be the first to flee buses, if they haven’t already.

Learn how to turn around bus ridership.

Widespread bus service cuts will degrade the quality of life for the millions of Americans who have no choice but to rely on transit, whether because they are low-income, or cannot drive for legal or medical reasons. The social costs of worsening bus service are manifold including lost jobs and missed medical appointments, lower retail spending, caregivers spending less time with children, and poorer public health outcomes. These impacts are not confined to metropolitan areas, either, as more than a million Americans in rural areas do not have a car.

The cruel injustice of these service cuts is that ensuring social distancing on transit requires more frequent service, not less. The post-COVID era requires us to operate transit not as a cost-optimized solution bent on serving the most passengers per trip, but rather, as an essential social utility that provides frequent service where it’s needed most but also enables social distancing on less-crowded vehicles.

Avoiding mass transit’s collapse, once and for all.

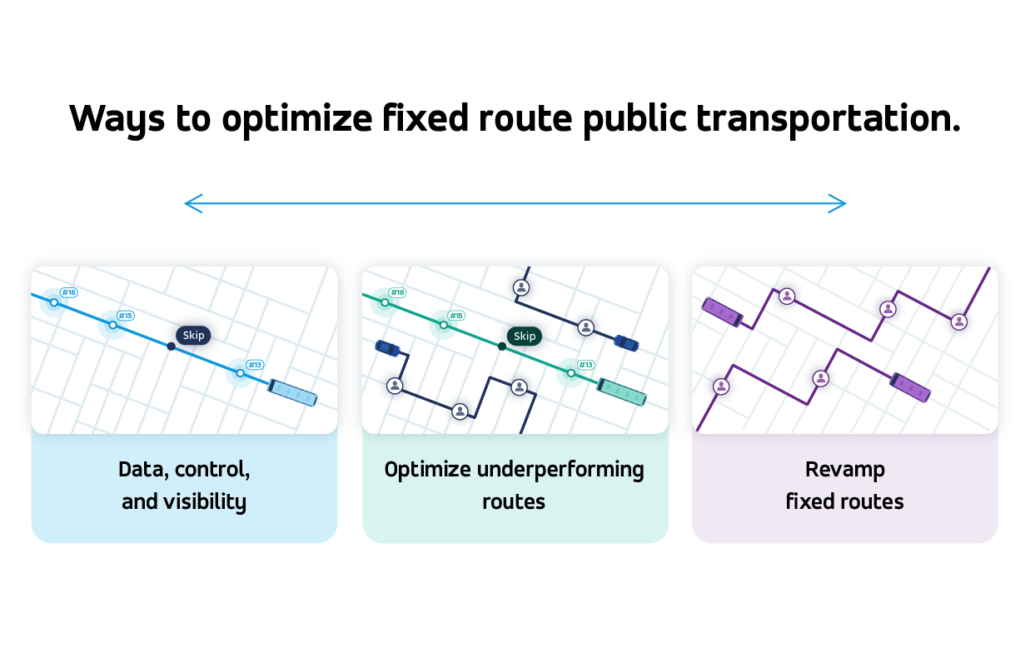

To avoid this bleak scenario, we must rework our transit systems to operate more effectively while responding to new demands, like social distancing. Despite seeing little innovation in nearly a century, mass transit has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to rebuild itself. Using new technology, it doesn’t have to be completely from scratch.

By blending together elements like dynamic routing algorithms, mobile payment methods, and demand-responsive service models, lots of good things are happening. Efficiency is improving. Wait times are decreasing. And most importantly, riders are returning. It may sound too good to be true, but innovative cities bold enough to take the plunge are being rewarded with some pretty impressive results.

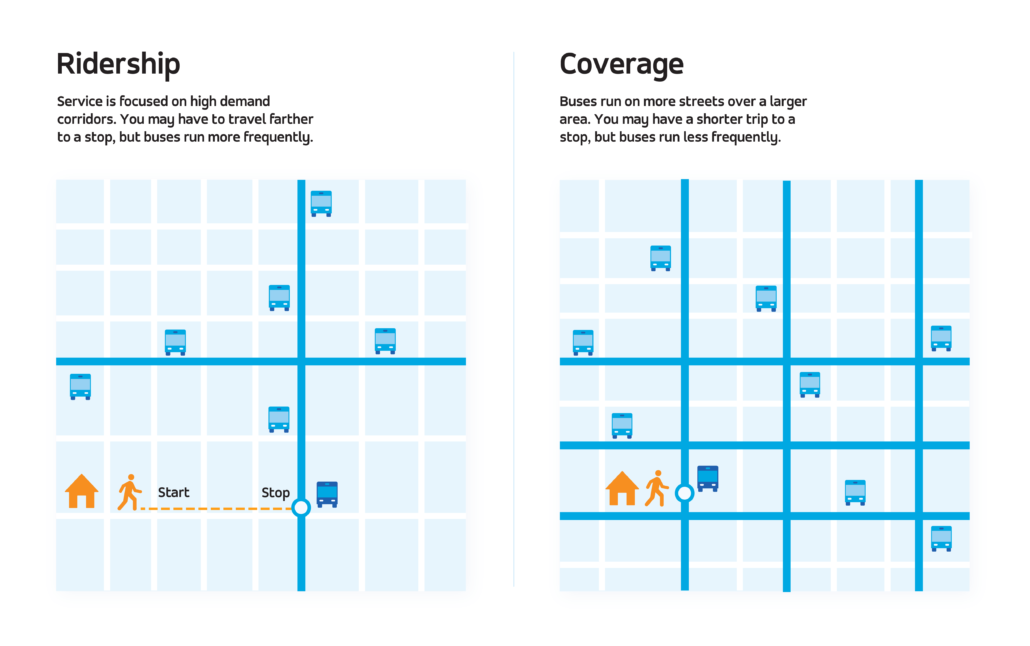

On top of recognizing the need for technology, every bus network must also finally address the classic tradeoff between serving coverage and serving ridership.

Rather than concentrating service on a handful of fast, frequent trunk lines where demand is the highest, too many bus systems feature a lattice widespread network of routes, but at low frequencies of 60 minutes or worse. Such low frequencies make travel times highly unreliable. Just as with your cell phone provider, there’s little value in “coverage” alone if the service quality is uniformly poor or unreliable.

Building a better bus network.

So what does a better bus network look like? Transit agencies from Los Angeles to Boston, New York, Miami, and the Bay Area are currently redesigning their bus systems to maximize ridership (and therefore their productivity), rather than providing ubiquitous but infrequent coverage to low-density places where transit is unlikely to thrive.

This approach involves concentrating fixed route bus service on the denser corridors where transit demand is highest. Increasing service in these areas will increase ridership and improve the operator’s cost-effectiveness. In the peripheral, lowest-density, or hard-to-serve areas of the network, fixed route bus service may not make sense altogether. These areas are often better served with flexible on-demand transit service in smaller vehicles, which provides superior service, with shorter wait times, and at lower cost to transit agencies.

Learn more about on-demand solutions.

The COVID-19 crisis is supercharging these efforts, as transit agencies can no longer justify the expense of inefficient service that provides a bare minimum of coverage but serves few people.

In Columbus, Ohio, the Central Ohio Transit Authority (COTA) is on the leading edge of this transformation. In 2017, COTA redesigned its fixed route system by cutting several inefficient, coverage-oriented routes and doubling the number of frequent, ridership-oriented trunk lines that run along the city’s denser corridors. These changes extended high-frequency bus service to an additional 100,000 residents for the first time.

COTA also increased weekend and evening service hours to better serve the needs of workers in the service and logistics industries, who typically do not follow traditional 9-5 commuting patterns. To fill in the network’s gaps where coverage-oriented service was reduced, COTA launched a series of on-demand transit services, ideal for shorter, locally-oriented trips or making first/last-mile connections to high-frequency lines.

The current crisis puts all transit agencies, but especially American bus systems, in dire straits. But the crisis is also a unique opportunity to redesign service that better meets riders’ needs. Leveraging innovative transit technologies and redesigning fixed route networks hold the key to transforming our bus systems to meet these new challenges.

.png?width=71&height=47&name=Sioux%20Falls%20Webinar%20(6).png)