Despite overhyped cries over a “public transportation death spiral,” we’re just now at the starting line of a once-in-a-generation race to rebuild our transportation networks. Take for instance the humble city bus. Despite seeing little innovation in nearly a century, bus networks are becoming a really attractive option in cities that are finally leveraging new TransitTech, making routes more efficient, convenient, and safer to ride while COVID-19 remains a risk.

By weaving together elements like dynamic routing algorithms, mobile payment methods, and demand-responsive service models, lots of good things are happening. Riders are returning. Efficiency is improving. Wait times are decreasing. It may sound too good to be true, but innovative cities bold enough to take the plunge are rewarded with some pretty impressive results.

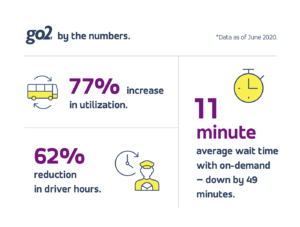

Take Sevenoaks. Two weeks was all it took for this town in Kent, UK, to totally transform its existing fixed-route bus network . COVID-19 caused ridership to plummet 90%, yet despite this drop, Sevenoaks saw some outstanding results from taking a fresh look at how public transportation could operate if you threw away the rulebook:

- 77% increase in utilisation.

- 62% reduction in driver hours.

- 46% reduction in miles driven.

- Average passenger wait times of 11 minutes, compared to the older route’s 60-minute frequency.

Let’s explore seven specific ways cities are using new technology to upgrade their transit networks:

1. Bus stops, now everywhere.

Curb-to-curb service is about as inefficient as it gets. By using demand aggregation technology, bus networks create “virtual bus stops” that ensure drivers take the most efficient routes by asking passengers to walk a short distance — though this distance is still far less than most riders walk to access fixed-route bus stops.

With virtual bus stops, riders are never out of range of the nearest bus stop, because the bus comes (most of the way to meet them) wherever they are. This improves customer satisfaction and reduces total journey times, leading to operational efficiencies (as seen in Sevenoaks) and lasting ridership gains.

2. Smarter payments = faster journeys.

Mobile fare payment improves not just driver safety by removing cash fareboxes and enabling rear-door boarding on larger buses; these measures also mean less time spent idling at the bus stop. New technology reduces the use of cash fare payment, while still providing options like prepaid debit cards or vending machine payments for riders without bank accounts or smartphones.

Since 2012, San Francisco has allowed all-door boarding throughout its bus system, resulting in reduced dwell times at bus stops of 38% and allowing the system to move buses faster even at a time of increasing traffic congestion. In London, the public transport authority stopped accepting cash in 2014, allowing it to redirect £24 million ($31 million) per year to additional bus service.

3. Contact tracing: you gotta know who’s on board.

Mobile fare payment also facilitates a critical need of the COVID-19 era: if a rider is known to be infected, reviewing transaction records allows authorities to instantly contact everyone who shared a vehicle with that person, critical to stopping the spread. Transit systems in Beijing and Seoul are already engaging with digital platforms, such as for fare payment or pre-trip bookings, to conduct contact tracing. In democratic societies, these platforms must comply with privacy regulations — such as by requiring informed consent — given the sensitive nature of riders’ health information.

4. A little distance makes a lot of sense.

Today’s bus networks need a way to automatically allow for social distancing. While transit agencies previously strived to carry as many passengers as possible, new transit technologies can cap the number of riders onboard (based either on pre-booking the ride or mobile fare payment records) to facilitate physical distancing based on a vehicle capacity. In the event riders are unable to board, the technology also has a fleet management platform, allowing managers to dispatch vehicles on-the-fly when additional capacity may be required during peak times.

5. Keep the bus moving.

If the bus is already at capacity, or if there aren’t any passengers requesting rides due to decreased demand, drivers can be instructed to skip stops entirely. This makes the service safer for passengers riding more popular bus routes while also making networks more operationally efficient, with the technology telling drivers exactly where to stop.

6. Knowing when to bow out.

Trip optimization and capacity planning aside, riders should also know when not to travel. Using the app that allows for contactless fare payments or pre-booking a ride, new transit technology can prompt passengers with a checklist. Do they have a fever? Are they wearing a mask? Results from the short Q&A could then dictate whether a passenger is allowed to book a ride or board the bus once it arrives.

7. Tech designed for multimodal trips.

While many transit agencies are getting better at providing multimodal trip information to customers, the solutions deployed so far are too fragmented to be effective. New transit technology can integrate with “Mobility as a Service” platforms to provide well-synchronized multimodal trips, which minimize wait times, again improving customer satisfaction. Unlike older approaches, which must develop customized apps at great expense for transit agencies, newer platforms have multimodal routing and access information baked into the system from the start.

These seven measures may seem daunting, but cities and transportation agencies don’t have to revamp their networks alone, or even all at once. Tackling the challenge from different angles, at different speeds if necessary, will undoubtedly prepare us for a future where public transit is once again safe, efficient, and shared.

.png?width=71&height=47&name=Sioux%20Falls%20Webinar%20(6).png)